This Time They Have Subtitles!

Reviews by Eleanor M. Farrell

Needless to say, it's winter yet again, and a good time to curl up with some mythopoeic video entertainment for those nights you still have power. It's okay to choose a movie over a book on occasion, especially since these foreign language offerings all require some literacy for those of who speak fewer than six languages! This selection demonstrates some very different cultural approaches to the fantastic; all are available on video and I hope will whet your appetites for further exploration.

A Chinese Ghost Story

(1987, Hong Kong) The first (and still among the best) of recent Hong Kong fantasy kung fu extravaganzas to find cult popularity in the U.S., this eye-popping film from director Ching Siu-tung combines doomed romance, spectacular martial arts, bloodcurdling evil sorcery and slapstick comedy in a lavishly photographed and thoroughly entertaining film. Leslie Cheung and Joey Wang are charmingly innocent as the inept young tax collector Ning and the lovely ghost who seeks his aid, while experienced monk Swordsman Yen (played by Ma Wu) provides supernatural assistance and some very odd Taoist rap lyrics. Supernatural adventures from the Hong Kong studios, incorporating elements of Chinese ghost tales, mythology and folklore, have now become a wildly popular staple of art film rep houses; A Chinese Ghost Story is a wonderful introduction to the genre. (Parts II and III are also available, but not quite as good -- II is fun but much more frenetic, with bandits impersonating ghosts, giant caterpillars, evil Buddhist priests, sword surfing and lots of slime. Other recommendations: Green Snake, The Bride with White Hair.)

(1987, Hong Kong) The first (and still among the best) of recent Hong Kong fantasy kung fu extravaganzas to find cult popularity in the U.S., this eye-popping film from director Ching Siu-tung combines doomed romance, spectacular martial arts, bloodcurdling evil sorcery and slapstick comedy in a lavishly photographed and thoroughly entertaining film. Leslie Cheung and Joey Wang are charmingly innocent as the inept young tax collector Ning and the lovely ghost who seeks his aid, while experienced monk Swordsman Yen (played by Ma Wu) provides supernatural assistance and some very odd Taoist rap lyrics. Supernatural adventures from the Hong Kong studios, incorporating elements of Chinese ghost tales, mythology and folklore, have now become a wildly popular staple of art film rep houses; A Chinese Ghost Story is a wonderful introduction to the genre. (Parts II and III are also available, but not quite as good -- II is fun but much more frenetic, with bandits impersonating ghosts, giant caterpillars, evil Buddhist priests, sword surfing and lots of slime. Other recommendations: Green Snake, The Bride with White Hair.)

Como Agua Para Chocolate (Like Water for Chocolate)

(1992, Mexico) Based on a novel by popular author Laura Esquivel, Alfonso Arau's film continues the tradition of magical realism which permeates modern Latin literature and cinema. Set in 1910 and narrated, apparantly by Esquivel, as a family legend, the movie relates the story of Tita, a young woman thwarted in love but whose passion, channeled into the food she cooks for her family, creates a magic which transforms all their lives. Tita's tears, when she learns that her lover Pedro has married her sister only to remain near, mingle with the wedding cake ingredients to make all of the guests weep. Later, Tita prepares a meal using roses Pedro has given her which is such an aphrodisiac that everyone at the table is aroused; Tita's middle sister Gertrudis actually sets a building on fire and is swept away, naked, by a passing bandolero. The film is lush, subtle and quite funny, with an originality stemming from the Spanish approach to magic as a natural force which can change the world when transmitted through real emotions. And the food! Como Agua Para Chocolate is a feast for all the senses.

Kwaidan

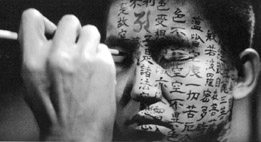

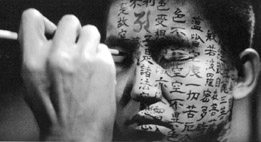

(1964, Japan) Masaki Kobayashi directed this film based on four tales written by American author Lafcadio Hearn, who lived for many years in China and Japan and was an enthusiastic student of folktales from both cultures. Each of the stories is atmospherically photographed and relates an eerie tale. The first episode, "The Black Hair" (based on Hearn's story "The Reconciliation"), tells of a poor samurai who leaves his good wife to win promotion in another city, but then regrets his choice and attempts, too late, to make amends. "Yuki-Onna" ("The Woman of the Snow"), a female ice demon, marries a woodcutter, in a tale very much like the European stories of fairy women and the restrictions placed on their couplings with mortal men. In "The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Ho´chi" a blind musician, who unknowingly plays music for a court of dead warriors, discovers his danger and is given supernatural protection, in the form of sacred texts painted over his entire body. Unfortunately, one small area is overlooked.... Finally, another samurai is haunted by the vision of a man seen reflected "In a Cup of Tea."

(1964, Japan) Masaki Kobayashi directed this film based on four tales written by American author Lafcadio Hearn, who lived for many years in China and Japan and was an enthusiastic student of folktales from both cultures. Each of the stories is atmospherically photographed and relates an eerie tale. The first episode, "The Black Hair" (based on Hearn's story "The Reconciliation"), tells of a poor samurai who leaves his good wife to win promotion in another city, but then regrets his choice and attempts, too late, to make amends. "Yuki-Onna" ("The Woman of the Snow"), a female ice demon, marries a woodcutter, in a tale very much like the European stories of fairy women and the restrictions placed on their couplings with mortal men. In "The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Ho´chi" a blind musician, who unknowingly plays music for a court of dead warriors, discovers his danger and is given supernatural protection, in the form of sacred texts painted over his entire body. Unfortunately, one small area is overlooked.... Finally, another samurai is haunted by the vision of a man seen reflected "In a Cup of Tea."

Peau d'Ane (Donkey Skin)

(1971, France) Jean Cocteau's classic Beauty and the Beast is by far the best-known French cinematic fantasy, but this later effort from director Jacques Demy, based on the Charles Perrault fairy tale, is also worth seeking out. Having promised his dying Queen to remarry only when he finds someone more beautiful than she, the grieving King finds that he only desires his own daughter. The girl, played by the lovely Catherine Deneuve, escapes with the help of her ditzy (very Zsa Zsa Gabor) fairy godmother, and disguises herself as a drudge wearing the skin of a magical donkey. Although Donkey Skin is scorned by everyone in her new surroundings, she does manage to charm the local Prince and eventually finds a happy ending. The film's cinematography is quite outstanding, with stylistic sets and overbrown costumes emphasizing the fantastic nature of the story without the need for special effects. Jean Marais, who portrayed Cocteau's Beast Prince, here takes the part of the incestuous King.

The Seventh Seal

(1959, Sweden) Director Ingmar Bergman's allegorical masterpiece still holds up well as an exploration of the meaning of life and suffering. A knight (played by Max von Sydow) returns with his squire from the Crusades to a land suffering from plague and anarchy. Meeting Death on the beach, the knight challenges the specter to a game of chess, as he attempts to discover God's purpose before he is taken. Meanwhile, the Knight and his companion befriend a company of players, and confront a variety of petty evils led by ignorance and greed, as their journey leads them to the Black Death. Bergman's black and white tableaux imagery has made this film a classic. If the theme is too downbeat for a winter evening, turn it into a double feature with Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey, in which our dimwitted heroes also challenge Death, this time to Clue and Twister.

(1959, Sweden) Director Ingmar Bergman's allegorical masterpiece still holds up well as an exploration of the meaning of life and suffering. A knight (played by Max von Sydow) returns with his squire from the Crusades to a land suffering from plague and anarchy. Meeting Death on the beach, the knight challenges the specter to a game of chess, as he attempts to discover God's purpose before he is taken. Meanwhile, the Knight and his companion befriend a company of players, and confront a variety of petty evils led by ignorance and greed, as their journey leads them to the Black Death. Bergman's black and white tableaux imagery has made this film a classic. If the theme is too downbeat for a winter evening, turn it into a double feature with Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey, in which our dimwitted heroes also challenge Death, this time to Clue and Twister.

The Shadow of the Raven

(1988, Iceland) This rather unique version of the Tristan and Isolde story from Icelandic director Harfn Gunlaugsson is set against the backdrop of Iceland's Christianization (which officially occurred, by parliamentary decree, in 1000 A.D.). The hero Trausti's father, a follower of Odin, has died, but his widow memorializes the death by building a Christian church. The film begins with Trausti's return from Norway with his education in the new religion and an Italian artist (the self-titled "Great Leonardo" who serves as both outside observer and comic relief) to paint the altar fresco. Arriving in the midst of a clan feud, Trausti takes responsibility, as clan leader, for the killing of Isolde's father by one of his men. Isolde scorns Trausti at first and demands revenge, but is eventually won over by his determination to make peace. The various elements of the doomed romance of the medieval lovers are greatly changed in this version; it is intriguing to view this familiar tale as a classic Icelandic epic, more akin to Njal's Saga than to medieval romance. One scene in particular reflects the saga tradition: the reconciliation and betrothal of Trausti and Isolde on a stone bridge is witnessed and recited by a group of old men, using a formal question and answer structure. Set this way, the scene is more effective than if done as straightforward action. Throughout the film, the Icelandic scenery is stunning, the costumes and sets authentic-looking, and the ensemble of Icelandic and Scandinavian actors competent and engaging. Most of all, this film is recommended as a fascinating study of medieval Icelandic society in transition, centering around the conflict between clan loyalty and the idea of a more universal brotherhood.

A version of this article originally appeared in the February 1999 issue of Mythprint.

Return to Film Index

ElectroEphemera Index

(1987, Hong Kong) The first (and still among the best) of recent Hong Kong fantasy kung fu extravaganzas to find cult popularity in the U.S., this eye-popping film from director Ching Siu-tung combines doomed romance, spectacular martial arts, bloodcurdling evil sorcery and slapstick comedy in a lavishly photographed and thoroughly entertaining film. Leslie Cheung and Joey Wang are charmingly innocent as the inept young tax collector Ning and the lovely ghost who seeks his aid, while experienced monk Swordsman Yen (played by Ma Wu) provides supernatural assistance and some very odd Taoist rap lyrics. Supernatural adventures from the Hong Kong studios, incorporating elements of Chinese ghost tales, mythology and folklore, have now become a wildly popular staple of art film rep houses; A Chinese Ghost Story is a wonderful introduction to the genre. (Parts II and III are also available, but not quite as good -- II is fun but much more frenetic, with bandits impersonating ghosts, giant caterpillars, evil Buddhist priests, sword surfing and lots of slime. Other recommendations: Green Snake, The Bride with White Hair.)

(1987, Hong Kong) The first (and still among the best) of recent Hong Kong fantasy kung fu extravaganzas to find cult popularity in the U.S., this eye-popping film from director Ching Siu-tung combines doomed romance, spectacular martial arts, bloodcurdling evil sorcery and slapstick comedy in a lavishly photographed and thoroughly entertaining film. Leslie Cheung and Joey Wang are charmingly innocent as the inept young tax collector Ning and the lovely ghost who seeks his aid, while experienced monk Swordsman Yen (played by Ma Wu) provides supernatural assistance and some very odd Taoist rap lyrics. Supernatural adventures from the Hong Kong studios, incorporating elements of Chinese ghost tales, mythology and folklore, have now become a wildly popular staple of art film rep houses; A Chinese Ghost Story is a wonderful introduction to the genre. (Parts II and III are also available, but not quite as good -- II is fun but much more frenetic, with bandits impersonating ghosts, giant caterpillars, evil Buddhist priests, sword surfing and lots of slime. Other recommendations: Green Snake, The Bride with White Hair.)

(1964, Japan) Masaki Kobayashi directed this film based on four tales written by American author Lafcadio Hearn, who lived for many years in China and Japan and was an enthusiastic student of folktales from both cultures. Each of the stories is atmospherically photographed and relates an eerie tale. The first episode, "The Black Hair" (based on Hearn's story "The Reconciliation"), tells of a poor samurai who leaves his good wife to win promotion in another city, but then regrets his choice and attempts, too late, to make amends. "Yuki-Onna" ("The Woman of the Snow"), a female ice demon, marries a woodcutter, in a tale very much like the European stories of fairy women and the restrictions placed on their couplings with mortal men. In "The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Ho´chi" a blind musician, who unknowingly plays music for a court of dead warriors, discovers his danger and is given supernatural protection, in the form of sacred texts painted over his entire body. Unfortunately, one small area is overlooked.... Finally, another samurai is haunted by the vision of a man seen reflected "In a Cup of Tea."

(1964, Japan) Masaki Kobayashi directed this film based on four tales written by American author Lafcadio Hearn, who lived for many years in China and Japan and was an enthusiastic student of folktales from both cultures. Each of the stories is atmospherically photographed and relates an eerie tale. The first episode, "The Black Hair" (based on Hearn's story "The Reconciliation"), tells of a poor samurai who leaves his good wife to win promotion in another city, but then regrets his choice and attempts, too late, to make amends. "Yuki-Onna" ("The Woman of the Snow"), a female ice demon, marries a woodcutter, in a tale very much like the European stories of fairy women and the restrictions placed on their couplings with mortal men. In "The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Ho´chi" a blind musician, who unknowingly plays music for a court of dead warriors, discovers his danger and is given supernatural protection, in the form of sacred texts painted over his entire body. Unfortunately, one small area is overlooked.... Finally, another samurai is haunted by the vision of a man seen reflected "In a Cup of Tea."

(1959, Sweden) Director Ingmar Bergman's allegorical masterpiece still holds up well as an exploration of the meaning of life and suffering. A knight (played by Max von Sydow) returns with his squire from the Crusades to a land suffering from plague and anarchy. Meeting Death on the beach, the knight challenges the specter to a game of chess, as he attempts to discover God's purpose before he is taken. Meanwhile, the Knight and his companion befriend a company of players, and confront a variety of petty evils led by ignorance and greed, as their journey leads them to the Black Death. Bergman's black and white tableaux imagery has made this film a classic. If the theme is too downbeat for a winter evening, turn it into a double feature with Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey, in which our dimwitted heroes also challenge Death, this time to Clue and Twister.

(1959, Sweden) Director Ingmar Bergman's allegorical masterpiece still holds up well as an exploration of the meaning of life and suffering. A knight (played by Max von Sydow) returns with his squire from the Crusades to a land suffering from plague and anarchy. Meeting Death on the beach, the knight challenges the specter to a game of chess, as he attempts to discover God's purpose before he is taken. Meanwhile, the Knight and his companion befriend a company of players, and confront a variety of petty evils led by ignorance and greed, as their journey leads them to the Black Death. Bergman's black and white tableaux imagery has made this film a classic. If the theme is too downbeat for a winter evening, turn it into a double feature with Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey, in which our dimwitted heroes also challenge Death, this time to Clue and Twister.